[Maarten Van Horenbeeck] [Risk Management]

Culture, ethnicity and their impact on risk communication

Maarten S.L.J.Vanhorenbeeck

maarten@daemon.be

Abstract

Cultural and ethnic diversity in society have sharply increased over the past years. Minority Hispanic groups within the US, as well as African ethnic groups in European cities have grown significantly. This paper identifies how contemporary risk communication, in order to be successful, needs to take these two aspects into account. It introduces the reader to a number of starting points related to cultural interpretation. It also finds that fragmentation of communications media is an important enabling factor in reaching the correct target audience, but also poses additional risk regarding the interpretation of its content.

Keywords: Risk; SARF; Cultural Theory; Ethnicity; Risk Communication

Introduction: Defining Culture and Ethnicity

Basic definitions of culture and ethnicity can be found in the Cambridge English dictionary. It prescribes culture as “the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time” and ethnicity as being “of a national or racial group of people” (Cambridge University Press, 2003). These however do not give us much insight in how best to approach diversity in society.

The concept of culture is most difficult. In recent literature, Michelle Lebaron describes cultural groups as entitities that centre “around a wide variety of shared identities, including race, ethnicity, age, nationality, geographical setting, socioeconomic class, able-bodiedness or disability, sexual orientation, language, religion, profession or job role, and gender” (Lebaron, 2003, p.10). This implies that a person does not belong to a single culture, but identifies with different types of cultures. She describes ‘cultural starting points’ as “beginnings from which thought and ideas are generated”. Keesing similarly defines culture as “the publicly available symbolic forms through which people experience and express meaning” (Keesing, 1974 in Swidler, 1986, p. 273).

While ethnicity is often considered as much more clear, there is significant discussion on its definition. Ethnic groups can be defined based on many variables such as country of birth, skin colour, religion or racial group. People of identical racial groups can be of very different religion. Abizadeh (2002) concludes that race is in fact a social construct.

Sufficient for this paper is to understand these two terms are used to identify certain groups of people within society. These groups can be defined by a large number of possible parameters. As such, there is risk for confusion and overlap between ethnicity and culture. It is significant that a number of theories and studies have appeared that indicate culture may be quite important in the correct understanding of a risk message.

Considerable attention has been given to the Theory of Cultural Complexity, a concept initially developed within the field of anthropology by Mary Douglas. The framework identifies four major ‘ways of life’: fatalism, hierarchy, individualism and egalitarianism. A culture is classified in each of these groups by measuring two dimensions: grid, or how regulated life within the culture is and group, how integrated the culture is in terms of social relations (Mars & Frosdick, 1997). Members classified within a certain culture have a very specific way of dealing with risk. For example, individualists tend to disregard risk as coincidence, while hierarchs relate it to disregard of the social ruleset.

In some cases these cultures can be mapped fairly accurately to people of certain ethnic origin. One such mapping, called the white male effect, indicates that “risks tend to be judged lower by men than by women and by white people than by people of colour” (Finucane et al., 2000, p. 159). Further research by Palmer (2003) indicated that this pattern is also accurate for Asian males in the US. Palmer also observed that there seems to be no white male effect for financial risk. To complicate matters even further, Weber and Hsee (1998) even identified further ethnic differences in the perception of financial risk: when posed with risky financial choices, Chinese respondents were shown to be less risk-averse than Americans.

Cultural theory has been criticized by, amongst others, Sjöberg (1998), who was unable to establish that cultural bias was a major factor in risk perception. A slightly different implementation was developed by Earle and Cvetkovich. They agree with the basic premise of cultural theory that ‘risk is culturally constructed’, but propose a cultural division between two cultural orientations, being cosmopolitanism and pluralism. The pluralist person is risk averse and well aware of his own culture and its limitations. The cosmopolitan person, on the other hand, is able to adjust his perception of the world based on a number of ‘cultural narratives’ (Earle & Cvetkovich, 1997).

Increased cultural diversity

There is significant evidence to show that many major western cities are becoming more diverse. We’ll review two cities in more detail, being New York and Brussels.

New York

New York is the largest city in the United States with a total of over 8 million inhabitants. Census data published in 2000 shows that of those 8 million, about 3.5 million were white, slightly more than 2 million was black and 787 047 people were of Asian origin. Over 300 000 people indicated they were of mixed race. In addition, over 2 million respondents indicated they were Hispanic or Latino (New York State, 2000). Similar census data from older periods of time is difficult to acquire, though research indicates there is indeed a significant trend towards more fracturization in the ethnic composition of the city (Moss, Townsend & Tobier, 1997).

This information gives a good indication of a city’s ethnic composition. It does not necessarily reflect the way that specific ethnic group is achieving critical mass: whether the ethnic group acts as one and is considered a significant player in society. An indicator here could be the way media approaches the ethnic group. In the city of New York, Arbitron, a radio listenership measurement organization, indicates that radio programming made for a Spanish speaking audience is growing significantly: as of Spring 2006, the second best listened to radio station in New York, is WSKQ, a station focusing on the Hispanic market (Arbitron, 2006)

Brussels

Brussels is a prime example of cultural differences. Natively, the city is bi-lingual French and Dutch, with a significant cultural difference between its Walloon and Flemish inhabitants. Added to this are a large number of immigrant groups. While the Belgian statistics office does not inquire as to the race of residents, it does make data available on foreign nationals.

A total of 307430 foreign nationals live within the borough of Brussels, out of a total of slightly more than 1 million residents. The largest groups are French (42750), Moroccan (41050), Spanish (19869), Italian (27233) and Turkish (11672). Naturally there are also large population groups from the previous colonies of Congo (10260) and Rwanda (1330) (FOD Binnenlandse Zaken, 2006).

Perhaps due to the limited size of their respective groups, radio and television programming for these minorities has not been a success in Belgium. Radio initiatives such as Contact Inter attempted to provide Arabic language programming but did not gain traction in the market (RTL, 2004). A different evolution is visible in the world of marketing. Cell phone providers such as BASE have added to their offering specific products aimed at certain population groups. “Ay Yildiz” and “Chiama” are pre-paid cellular products prepared specifically for Turkish and Italian community groups. They are also marketed in their respective languages.

Risk communication and its targets

Zimmerman (1987, p.1) identifies three goals for risk communication: to “(1) educate for the purpose of changing perceptions, attitudes and beliefs about risks and consequently achieving behaviour modifications toward risk; (2) to build consensus and (3) to educate or disclose information without expectations about quality of learning or ability to influence”. Implied in goals one and two is that risk communication solicits action. As such, it is highly critical that the communication is clear in its expectations and intended goal. In addition, transmitting the message to the recipient is also an important risk communication aspect.

Reaching the correct targets seems to have become more difficult. Kenneth Thompson investigated the use of media by an ethnic minority group, South Asians, and identified that in contrary to initial expectations – immigrants gradually immersing into the host culture – they in fact imported their culture through virtual communities, making use of modern media such as the internet. An increase in financial means even allowed families to provide more ethnic education for their children (Thompson, 2002).

While some of these ethnic groups have their own mass media outlets that can be used for risk communication, many are too small for such facilities. For example, creating a mass media outlet for the 1330 person large Rwandan community in Brussels is unlikely to be economically viable. Nevertheless, this community may be best addressed in its native language of Kinya-rwanda, and perhaps only partially understands French or English. In addition, Rwanda has known an upsurge in its Muslim community over the last decade. While Belgium does not register the faith of immigrant groups, it can be expected that such increase trickles through at the level of immigration into Brussels as well.

This poses practical problems: to perform accurate and successful direct risk communication to this group, government may prefer alternate communication channels. As such, the government would need to keep track of those media that actually reach smaller groups of people. This could include community groups.

Social amplification of Risk and ethnicity

The Social Amplification of Risk framework (SARF)

The Social Amplification of Risk framework was developed in 1988 by Kasperson, Renn and Slovic. It is a comprehensive framework that introduces the concept of a risk signal as interpretation of risk, and how it can be amplified and attenuated dynamically by social entities. Amplification could result in ‘ripple effects’ being generated outwards from the community of people affected (Kasperson, Kasperson, Pidgeon & Slovic, 2003).

Most contemporary texts refer to mass media as amplifiers of risk. Research has shown that mass media is however more active in agenda setting than educating the consumer on the risk (Dunwoody, 1992). Agenda setting can still be quite powerful in itself: it defines what people talk about with others. As such it can most definitely encourage amplification.

While this discussion is outside the control of the medium, the initial information provided is significant. Persuasion theory shows how even small bits of information can have a lasting influence. For example, the principles of inoculation theory indicate that when a statement is put forward, mild attacking arguments that are immediately refuted strengthen the statement against future attack (McGuire & Papageorgis, 1961 cited in Severin & Tankard). This provides some indication that information can be hardened against future attenuation.

Outside regular media, there are other entities in society that can have an amplifying role. A brief example can be found in the field of genetically modified food products. As a new type of biotechnology that has not yet been absolutely proven to be safe, there is quite some discussion and even protest against its implementation. Some examples of societal amplifiers in this example are government organizations, private organizations and religious entities.

Government organizations such as the American Food and Drug Authority sponsor research into genetically modified food products and make certain risk related decisions, e.g. as to whether or not require specific labelling for such food. Private organisations that operate at a grassroots level can intently increase their coverage of a certain issue and as such amplify that risk. The Organic Consumers Association, for example, gathers information from popular studies and spreads it to consumers through media or its website. Commercial organizations can undertake similar actions to attenuate the risk signal within society, hoping to boost sales and increase acceptance of its technology.

Even religious entities could perform this role. In 2003, the Vatican published a statement considering genetically modified foods as an answer to starvation (Cathnews, 2003). This likely impacted risk perception amongst its constituency.

Amplification and credibility

Peters, Covello and McCallum (1996) found “that defying a negative stereotype is key to improving perceptions of trust and credibility”. Such stereotypes differ by the structure of the organization. A commercial organization becomes more credible to the recipient when it displays concern and care for society. Governments on the other hand should show “commitment”, while “knowledge and expertise” were required for a grassroots community group.

The concept of expertise is closely bound to the subject matter and less to cultural differences. This is not the case for commitment and care. Becker (1960, p.32) describes commitments “come into being when a person, by making a side bet, links extraneous interests with a consistent line of activity”.

Values, or interests, are as such involved. These values are highly likely to be influenced by culture. A government can commit to providing its constituency with ‘meaningful life opportunities’. Some cultural groups within the populations may consider the ability to obtain affordable food, regardless of whether it was genetically modified or not, while others consider the purity of food and the protection against a yet unmeasured risk to be more important.

New opportunities and threats in risk communication

Media selection

Increased diversity obviously has a significant impact on how risk communication is performed. There is room for improvement both in message and medium. Focusing on individual ethnic groups allows for more powerful messages to be crafted. When sending a single message through mass media, it is necessary to cater to the interests and requirements of very different ethnical groups that are potential recipients. By including too much content, or flattening content to make it more acceptable to all potential recipients, the message may become ineffective or may not appeal sufficiently to action.

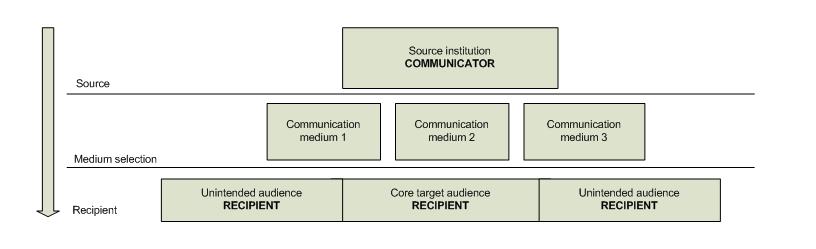

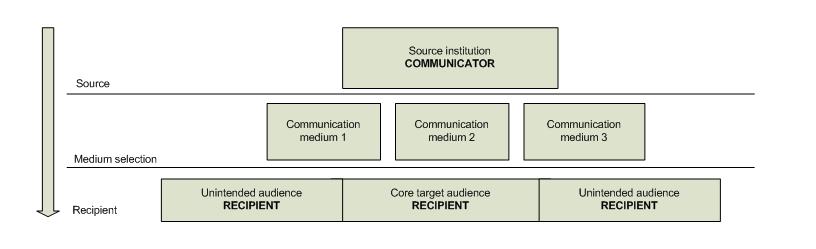

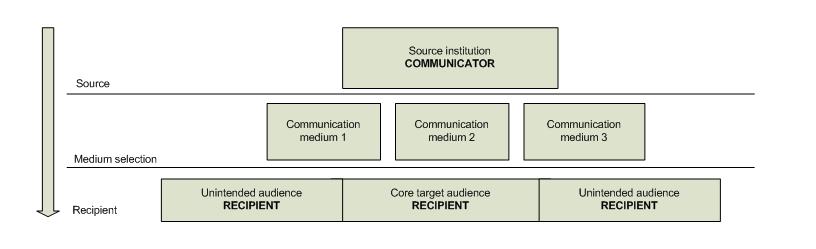

With the advent of more diverse media it has become possible to transmit many individual messages, targeted to individual target groups. These messages can contain solely information that resonates with the group, resulting in effective risk communication. An example is displayed in the below image.

Organizations sending out risk communication are no longer able to use one medium to get their message across to their target audience. Instead, they need to select from the media available in order to cover their complete target audience.

This creates additional threats: in the image above the target audience can only be reached by using the three available media outlets. However, medium 1 and 2 reach other groups outside the target audience. This complicates risk communication.

If the target audience is fully Christian, for example, certain metaphors can be used that resonate with a Christian recipient, but may be insulting to a Muslim audience. Such message could be acceptable to Medium 2, if it was a Christian radio station. Medium 1 and 2, both mainstream radio stations, may not accept the message, or if accepted, it could have an adverse effect.

Message fragmentation

When limited mass media was the sole medium on offer, it was feasible to perform media monitoring to ensure correctness of the message transfer. If necessary, an organization could demand a response to be published. With the diversity of today’s audience, a single message could become fragmented in several parts – each making it onto the media outlet most applicable to its cultural group.

In a well-known recent example, the pope addressed an audience at the University of Regensburg on September 12th, 2006, stating the following:

“… he addresses his interlocutor with a startling brusqueness, a brusqueness that we find unacceptable, on the central question about the relationship between religion and violence in general, saying: Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.” (Vatican, 2006).

Shortly after the conference, this statement caused significant outrage in the Muslim world (Abdelhadi, 2006). While the full paragraph shows a disagreement between the lecturer and the original writer of the cited material, specific media outlets chose purely to relay that part of the message with most impact, the forceful citation. Some yet-to-be investigated cultural issues may apply as well. Certain societies may consider the initial denying statement and the following citation as equally important. Other societies to which the citation may be more directly applicable may consider it inappropriate to mention the citation at all.

Assessing the cultural impact of risk communication

As shown, a large amount of parameters that can influence the social perception of risk. Each of these issues needs to be dealt with effectively while conducting risk communication. They concentrate on three different levels:

- Selection of the medium to channel the risk message: Which media allow us to spread our message efficiently to our intended target audience? How can we limit ‘spread’ of the message outside the core target audience?

- Content of the risk message: Which content offers us the best opportunity to have our risk message noticed by the target audience? What information does the target audience require to act?

- Interpretation of the risk message by the target: How can we ensure that our message does not invoke negative feelings from possible secondary audiences? What type of alternate information does the recipient require to establish a trustworthy image of us?

While some of these can be assessed based on the available studies and literature, specific message content will always need to be verified by representatives from the specific cultural target audiences.

Conclusion

This paper provided a basic introduction into some of the theory that underlies risk communication in culturally diverse environments. It identified that a significant increase of minority groups in major cities such as New York and Brussels is leading to critical mass: a point at which the members of cultural groups interact and form communities within society. It touched on Theory of Cultural Complexity to identify differences in the perception of risk, as well as how some of its classifications may match with existing ethnic groups.

Social Amplification of Risk was reviewed from the point of view of contemporary media, which in itself is becoming more diverse to match specific groups of society. The paper identifies some challenges and opportunities in using these smaller, but more directed media outlets for risk communication.

References

Abdelhadi (2006) Muslims debate Pope’s speech reaction. BBC News Online. London: BBC News. Retrieved 10th October, 2006 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/5378606.stm

Abizadeh (2002) Ethnicity, Race and Social Construct. World Order. 33.1 (2001): pp. 23-34

Arbitron (2006) New York Arbitron Ratings. New York: Arbitron. Retrieved 5th October, 2006 from http://www.arbitron.com.

Becker (1960) Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 66, No. 1 (July 1960). pp. 32-40. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cambridge University Press (2003) Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cathnews (2003) Vatican believes GM food could solve world hunger. Cathnews. Crows Nest NSW: Church Resources. Retrieved 25th September 2006 from http://www.cathnews.com/news/308/18.php

Dunwoody, S. (1992). The Media and Public Perceptions of Risk: How Journalists Frame Risk Stories. The Social Response to Environmental Risk Policy Formulation in an Age of Uncertainty. New York: Springer Publishing Company

Earle, T. & Cvetkovich, G. (1997) Culture, Cosmopolitanism, and Risk Management. Risk Analysis, Vol. 17, No. 1. McLean: Society for Risk Analysis.

Finucane, M., Slovic, P., Mertz, C.K., Flynn, J. & Satterfield, T. (1994) Gender, race and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society, Vol. 2, No. 2 (July 1, 2000), pp. 159-172. . Taylor & Francis.

FOD Binnenlandse Zaken (2006). Statistieken vreemdelingen / Nationaliteiten per arrondissement. Brussels: FOD Binnenlandse Zaken/Dienst Vreemdelingenzaken. Retrieved 4th of October, 2006 from http://www.dofi.fgov.be/nl/statistieken/Stat_ETR_nl.htm

Lebaron, M. (2003) Bridging cultural conflicts: a new approach for a changing world. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mars, G. & Frosdick, S. (1997) Operationalising the Theory of Cultural Complexity: A practical approach to risk perceptions and workplace behaviours. International Journal of Risk, Security and Crime Prevention. 1997. pp. 115-129.

Moss, M., Townsend, A. & Tobier, E. (1997). Immigration is transforming New York City. New York: New York University. Retrieved 10th of October, 2006 from http://urban.nyu.edu/research/immigrants/immigration.pdf

New York State (2000). Census 2000 Demographic Profiles. New York, NY: New York State Data Center. Retrieved 20th of September, 2006 from http://www.empire.state.ny.us/nysdc/census2000/DemoProfiles1.asp

Palmer, C. (2003). Risk perception: another look at the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2003, pp. 72-83. Taylor & Francis.

Peters, R., Covello, V. & McCallum, B. (1996). The Determinants of Trust and Credibility in Environmental Risk Communication: An Empirical Study. Risk Analysis, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1997). McLean: Society for Risk Analysis.

Pidgeon, Kasperson, Kasperson and Slovic (2003). The social amplification of risk: assessing fifteen years of research and theory. The Social Amplification of Risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp 13-46

RTL (2004). RTL Group: Annual Report 2004. Luxembourg: RTL Group. Retrieved 25th of September, 2006 from http://www.rtlgroup.com/files/AR_2004_RTLGroup_BELGIUM.pdf

Severin & Tankard (1997), Theories of Persuasion. Communication Theories, 4th edition, 197-214.

Sjöberg, L. (1998). World Views, Political Attitudes and Risk Perception. Risk: Health, Safety & Environment 137 [Spring 1998]. Concord: Franklin Pierce Law Center.

Swidler, A. (1986) Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. American Sociological Review Vol. 51 No. 2. pp.273-286. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Thompson, K. (2002). Border crossings and Diasporic Identities: Media Use and Leisure Practices of an Ethnic Minority. Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Fall 2002). Amsterdam: Springer Netherlands.

Vatican (2006), Meeting with the representatives of science at the University of Regensburg. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved October 10th, 2006 from http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/speeches/2006/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20060912_university-regensburg_en.html#_ftnref3

Weber, E. & Hsee, C (1998). Cross-cultured Differences in Risk Perception, but Cross-Cultural Similarities in Attitudes towards Perceived Risk. Management Science, 1998. Vol 44, No. 9 (September 1998), pp. 1205-1217. Linthicum, MD: INFORMS

Zimmerman, R. (1987). A Process Framework for Risk Communication. Science, Technology & Human Values. Vol. 12, No. 3/4 pp.131-137. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications